Using a combination of traditional verse and prose poetry, Jose Hernandez Diaz explores his Mexican-American Identity, art, language, and the absurdity of life

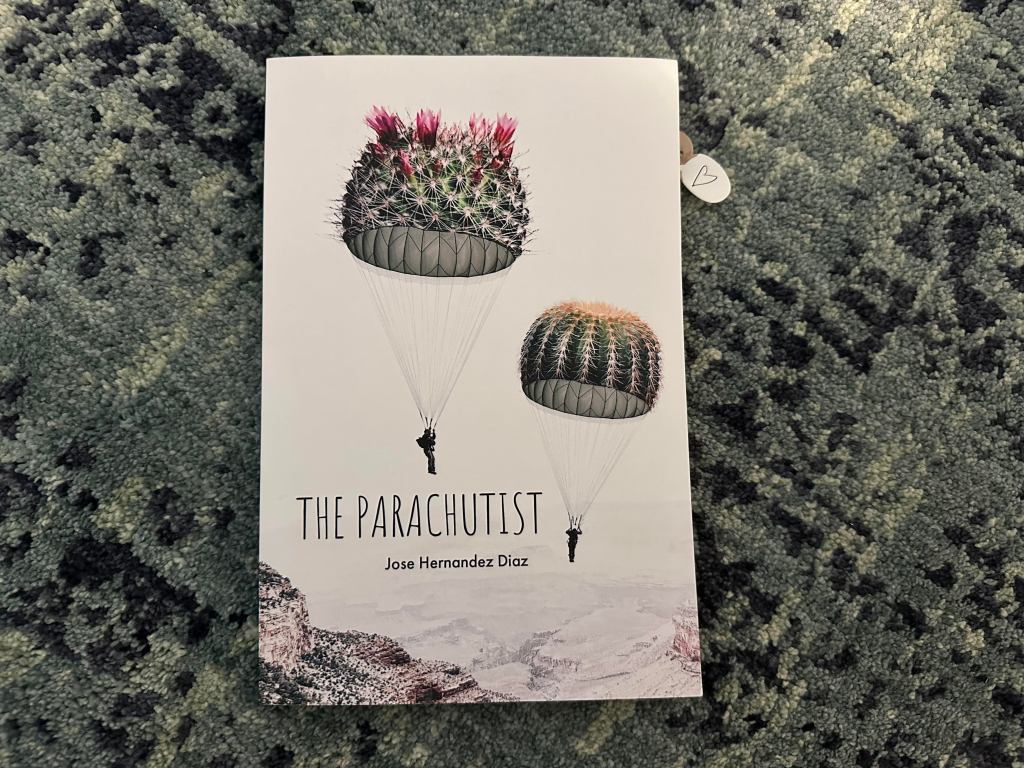

In the title prose poem of The Parachutist, Jose Hernandez Diaz portrays a man waging war against the mundane. And that’s what this collection does in every piece. Through explorations of how and why we become who we become, from origin to opportunity, Hernandez Diaz contrasts the hyperreal with the surreal to highlight the absurdity of what we live every day.

Hernandez Diaz opens with his family, portraying his parents and their quirks and victories against the odds. From the perspective of living in an intergenerational household with his aging father, he centers his parents’ roots in Guanajuato, Mexico, imagining what they could have become in different circumstances and examining their efforts to learn English against his own learning Spanish and Nahuatl as a heritage speaker.

In this first section, written in verse, Hernandez Diaz dissects the etymology. In “Cuate,” he explores the Mexican word for fraternal twins, using his twin brother’s vastly different path to more deeply examine what effect opportunity and experiences have on one’s outcome in life.

The next three sections use prose poetry to paint surreal scenes of everyday life. The first, offering vignettes of “a man in a Pink Floyd Shirt,” contains odes to visual artists including Goya and Van Gogh and the fitting portrait of modern politics “When the Government Wasn’t Run by Clowns,” in which “one must be 5.88 trillion years old to run for office.”

In the second section of prose poetry, Hernandez Diaz writes from a first-person perspective, often engaging with animals—real and mythological—with religious significance. In “The Centaur,” the title creature gatekeepers the speaker’s access to heaven for not having the right form of ID in a timely allegory for other border checkpoints. The speaker then tries on different human identities, including a man working at a windmill farm, continuing Hernandez Diaz’ ode to artists with one to Cervantes.

In the third prose section, Hernandez Diaz includes an ode to his first collection of poetry, “The Fire Eater,” before following “a skeleton” in the final part. He ends, again, with the duality of people and Latinidad in the story of a man getting a tattoo of Moctezuma. In the tattoo, “The skin of Moctezuma is dark brown like the man’s skin color. The man gets the tattoo on his forearm, to show strength. On the other forearm, he has a tattoo of Hernán Cortés with a sword, to show symmetry.” Through these explorations of language, opportunity, epigenetics, and mestizaje, Hernandez Diaz looks at identity from every facet. In The Parachutist’s world, you can’t understand the absurdity, hilarious and tragic, that Hernandez Diaz’ characters face in his prose poems without his exploration of identity development in verse in the first section. And because of this thoroughness, The Parachutist has something to offer any American reader, whether they identify with Hernandez Diaz watching his parents age, his parents’ journeys as immigrants, his relearning of language, or simply the strange experiences we all have that result from the very processes Hernandez Diaz examines and how they make us who we are.

Leave a comment